How Analytics Tools & AI Can Subtly Distort Our Understanding

Why even data-driven organisations fall into false certainty – and how to detect the three hidden traps.

In October 2023, Israel’s defense intelligence system, considered one of the most advanced in the world, failed to foresee or prevent a massive surprise attack.

This wasn’t a failure to collect information. On the contrary - the system had unparalleled access to digital signals, intercepted communications, satellite imagery, and predictive models powered by cutting-edge AI. It was backed by vast investment, years of machine learning, and top analytical talent. And yet, it missed its core purpose - to detect and alert in time before a known threat escalated.

How did it happen? Because Israel's intelligence fell into “Data Morgana” - a conceptual takeoff on the term Fata Morgana, the mirage that appears real until you get close. Just like its optical namesake, Data Morgana creates a false sense of certainty, like an image of an oasis in the desert that vanishes as we approach.

Data Morgana is a seductive illusion of clarity, appearing when data looks complete, coherent and even self-explanatory. It makes us feel we fully understand a situation, even when we don’t.

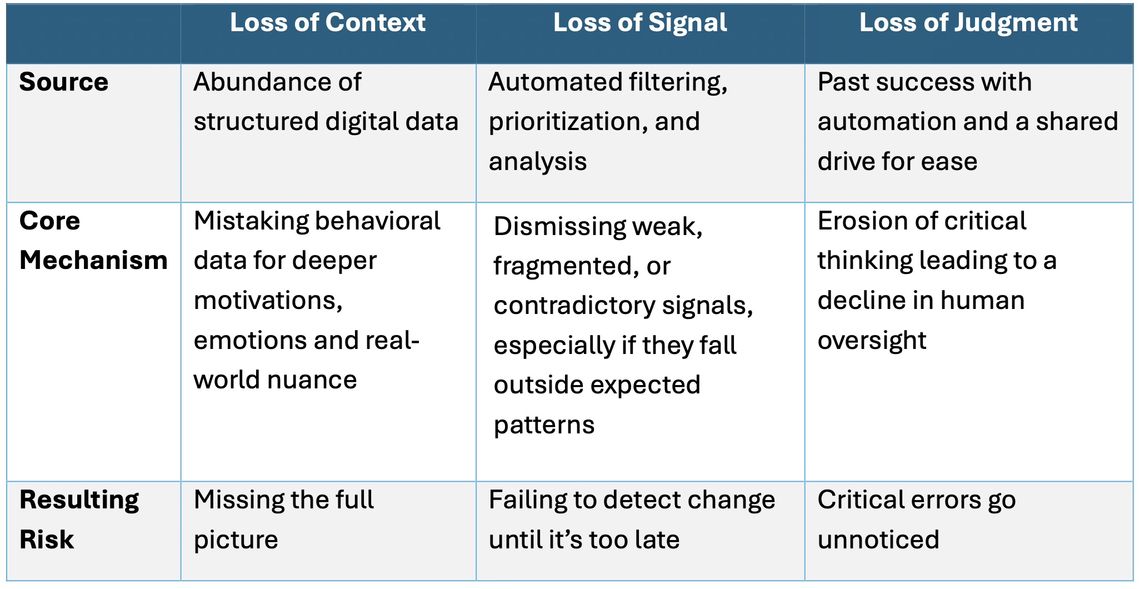

This paper examines three intertwined cognitive traps that cloud perception. Each rooted in a different type of distortion, yet all reinforcing the same illusion of understanding:

We draw on this national intelligence failure not only because of its gravity, but because it offers a striking early warning.

A strategic risk is now emerging across all decision-making environments, especially in corporate settings: the growing reliance on digital data, predictive models, and automated analysis to understand human complexity and guideexecutive decisions.

Through real-world business examples, we explore how each of these cognitive traps manifest and what leaders, strategists, and insight teams can do about it. After all, if a system with near-unlimited resources, data, and top-tier AI failed to see clearly, it’s worth asking what blind spots we might be missing.

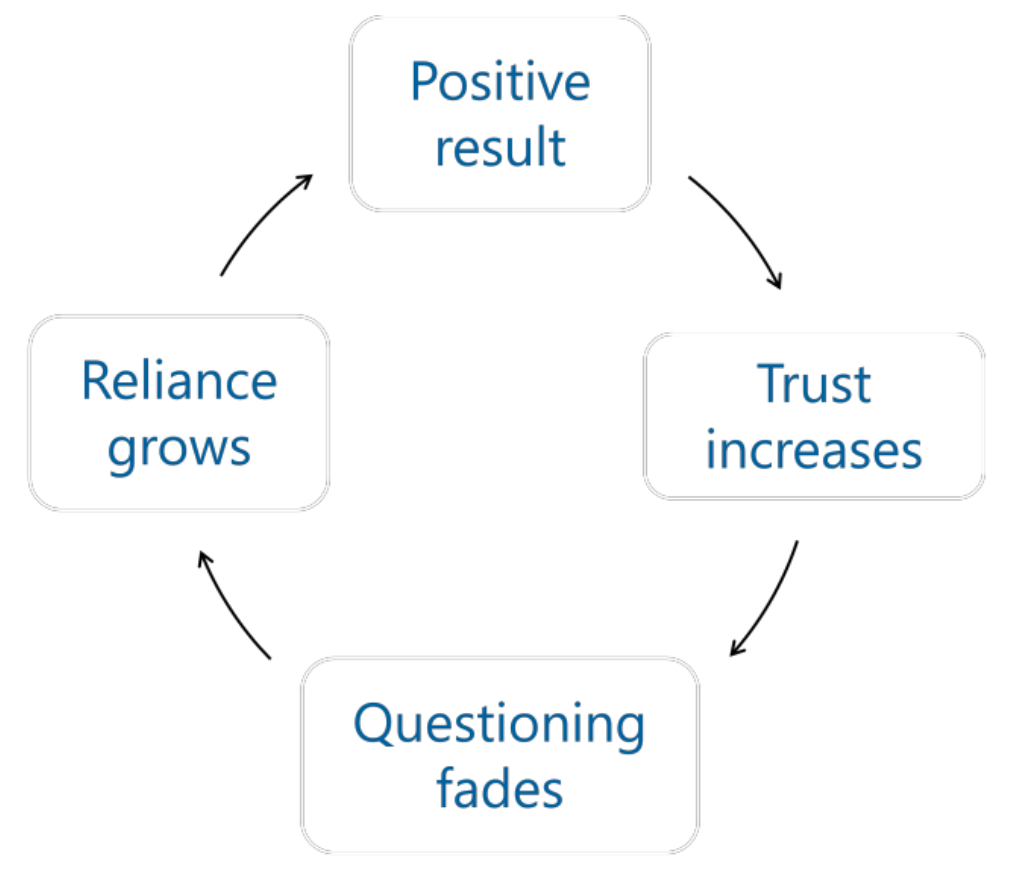

Table 1 - The 3 Losses Behind Data Morgana – How Understanding Gets Distorted

Table 1 - The 3 Losses Behind Data Morgana – How Understanding Gets Distorted

Loss of Context – When dashboards hide the real world

Loss of Context occurs because accurate, structured digital data is detached from the messy, situational reality it’s meant to represent. In environments driven by standardized metrics such as conversion rates, CRM funnels, and the continuous measurement of digital behaviors, organizations often confuse the map for the terrain. They begin to treat data as reality, rather than a filtered translation of it. This confusion grows deeper as automation speeds up reporting, making it even harder to notice when depth is missing behind the numbers.

At the heart of this loss lies a simple truth: behavioral data is only the visible tip of a much deeper psychological and situational iceberg. It tells us what people did - not why they did it, not how they felt, not what they noticed and chose not to act on, and certainly not what they might do next.

Without human framing, behavioral signals are easily misread. Personality traits, emotional states, timing, power dynamics, and local conditions all shape human decisions. That’s why structured dashboards without sufficient context often lead to shallow insights and poor predictions.

To influence effectively, we must understand both patterns and the deeper forces behind them: motivations, inhibitions, and mental models (the implicit ways people interpret, prioritize, and respond to what they see). Even when digital data reveals a clear trend, the meaning behind it - the why - can remain opaque. And without this deeper layer, attempts to act or influence tend to miss the mark.

This disconnect mirrors what psychologists Rozenblit and Keil (2002) called the illusion of explanatory depth - the belief that we fully grasp how something works simply because we've seen a simplified version of it. Their research showed that people usually overestimate their understanding of complex systems, until they’re asked to explain them in detail. Structured digital data can create the same effect. The cleaner and more coherent it looks, the more confident we feel in our understanding - even when this understanding is shallow.

That’s why direct human engagement (observing, listening, probing) remains irreplaceable

The consequences of this illusion became devastatingly evident in the Israeli intelligence failure of 2023.

In the years leading up to the attack, Israel had extensive surveillance capabilities. The system collected vast amounts of behavioral data: movements were tracked, patterns were analyzed, and anomalies were logged.

Due to operational complexity and security risks, human intelligence sources on the ground (HUMINT) were gradually reduced, while language and cultural experts were scaled back for cost-efficiency reasons. Both reductions were made under the belief that digital monitoring would be sufficient.

The digital behavioral data, however, could be interpreted in multiple ways: as routine, mere noise, or potential escalation.

Some worrying information did surface, yet without human presence or deep interpretation, there was no access to the underlying intentions, motivations, or shifting cultural and political aspirations.

In other words, the human context was lost.

This gap between data and reality isn’t limited to security. In organizational settings, the same mechanism applies. When decision-makers are physically or mentally disconnected from the field, their understanding of the data begins to drift away from real-world dynamics. This isn’t a data problem; it’s a growing difficulty in understanding the full picture.

Netflix offers a vivid example from the business world.

Netflix – Loss of Context

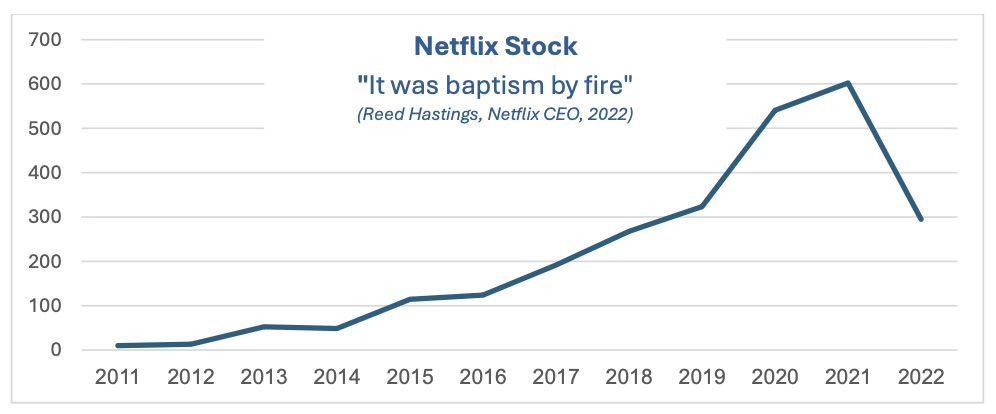

Netflix was the company that saw the future before anyone else. It pioneered streaming, disrupted the entertainment industry, and set new standards for the way people consume content. However, in the first half of 2022, it lost over one million subscribers - its first major drop in more than a decade.

As a result, the company suffered a sharp decline of over 50 percent in its stock value, falling from a peak of $700 in November 2021 to $337 in April 2022.

Figure 1. Netflix Share Price (2011–2022)

Figure 1. Netflix Share Price (2011–2022)

This wasn’t just a market fluctuation. It reflected a deeper failure to read the gradual shifts that followed COVID-19 lockdowns. As people returned to work and spent more time outside their homes, entertainment habits began to change. Streaming became just one option among many, and price sensitivity for these services began to grow. While Netflix raised subscription prices, competitors such as Amazon Prime and Disney+ responded with more flexible or affordable offers.

One of the reasons Netflix was late to recognize the shift was that behavioral data still looked strong.

Big-budget titles like Red Notice and The Gray Man continued to drive high numbers, reinforcing the impression that loyalty remained unwavering. Total viewing also seemed strong, as multiple users were watching under a single subscription - overstating actual usage per paying customer.

But underneath, these internal indicators masked a deeper shift: users’ motivations and preferences were changing.

As Netflix itself admitted in a Letter to Shareholders, the company had operated under a “COVID cloud” and overestimated continued growth based on pandemic-era behavior patterns.

Netflix experienced a loss of context.

The data showed what people were doing on the platform but not what it meant, namely how behaviors and expectations were shifting in the outside world. Their data looked clear - and that’s exactly what made true understanding so easy to miss.

Loss of Signal: When Machines Miss the Message

Loss of Signal occurs because algorithms treat contradictions as noise, overlook weak or ambiguous inputs and dismiss the unexpected. Even in data-rich environments, some of the most critical cues remain faint, fragmented, or inconsistent - and these are often the very signals that could matter most.

As data processing becomes increasingly automated, many critical steps in analysis including classification, prioritization, pattern recognition, and even basic interpretation are now handled by algorithms and AI systems. But automation doesn’t just shift who does the work, it also reshapes how it’s done.

The source of this loss lies in how these systems process information:

They rely on the past. Machine learning models are trained on historical data. This makes them extremely effective at recognizing recurring patterns; however they are also prone to discounting early signs of change. When a pattern is subtle, or hasn’t happened before, the automated system is likely to downplay or completely ignore it. People, in contrast, are wired to notice deviation. Our survival once depended on detecting slight changes in environment or behavior. This ability helps us pick up on early signals of danger before they escalate into real threats.

They work within predefined parameters. Automated systems are designed to classify inputs based on fixed structures and predefined categories. Anything that doesn’t fit such as ambiguity, contradiction, or weak signals, tends to be ignored or discarded as noise. Human thinking is more flexible. We can hold contradictions, tolerate uncertainty, and explore meaning even before it’s clear if there’s any underlying logic at all.

They lack deep cultural and emotional understanding. Machines struggle with cues that carry emotional weight, cultural nuance, or interpersonal meaning. Irony, sarcasm, hesitation, silence, or minor shifts in tone are hard to quantify and in many cases, go unnoticed or misinterpreted. Even when emotion is detected, machines often fail to recognize in what ways it unfolds over time, missing build-up, escalation, or other changes. Humans evolved to read emotion in others by picking up on voice, posture, and micro-expressions. We instinctively track emotional development, even without a single word.

They can hallucinate when data is missing or ambiguous.

In the absence of clear input, some AI systems produce confident-sounding but inaccurate outputs, filling in gaps with fabricated conclusions.

Humans, in contrast, tend to pause or reflect when information is unclear. Uncertainty often leads people to deeper inquiry, allowing us to seek meaning instead of inventing it.

Together, these limitations create a dangerous blind spot: the system sees what it’s built to see and misses what it’s not.

The cost of this blind spot came into full view in the Israeli intelligence failure of 2023.

When the other side adopted deception tactics and stopped using digital communication channels, the automated systems were left effectively blind. They simply failed to recognize the absence of digital signals as a potential red flag. There was no visibility into operational intent, no awareness of short-term plans.

A few fragmented indicators did surface before the attack – but they were faint, contradictory, and difficult to interpret. These subtle cues didn’t align with the patterns the automated models had been trained to detect or able to integrate into a high-risk, time-sensitive threat.

The signals were there however, they fell outside what the system could process or interpret.

Nike offers a telling case from the business world.

Nike Loss of Signal

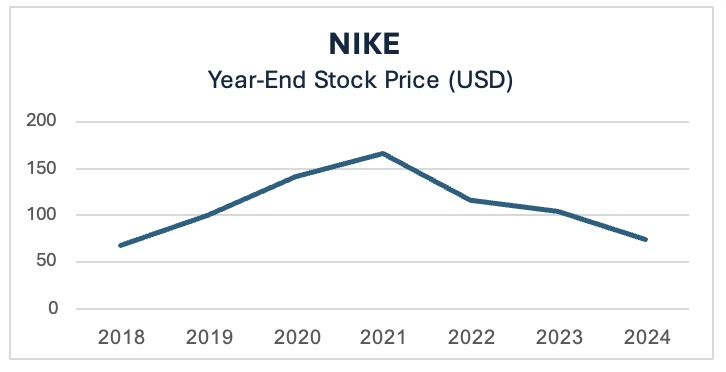

In a very different setting, in 2023, Nike experienced a setback: net income dropped 16%. In 2024 after several years of 2 digits growth, digital sales declined 3%, and the brand’s cultural edge, once synonymous with athletic trend leadership, began to fade.

The share price illustrates the story: from a peak of $167 in 2021, Nike lost over half its market value by the end of 2024, reflecting investor concern.

Figure 2 - Nike Share Price (2018-2024)

Figure 2 - Nike Share Price (2018-2024)

Table 2- Nike’s Digital Sales Growth (2021–2024)

Table 2- Nike’s Digital Sales Growth (2021–2024)

At the root was a bold strategic shift: a deliberate pivot away from wholesale partners in favor of a direct-to-consumer (DTC) model built around Nike’s own digital platforms. The goal was to gain control, loyalty, and better data. Still, the more it focused on its own ecosystem, the more it lost signal of what was happening beyond it.

Because Nike had scaled back its wholesale partnerships, it had much less access to what was happening on the ground. It didn’t hear the early complaints about product fatigue. It didn’t notice when interest near its shelf space began to decline. It missed the early signs that certain designs weren’t resonating, or that regional preferences were changing. These signals were mostly visible on the retail floor - outside the channels Nike had chosen to prioritize.

Their view of the consumer came through owned digital platforms, which meant that anyone who didn’t engage, or merely lost interest, fell off the radar.

However, some scattered signs of brand erosion did appear, but they were overshadowed by solid short-term performance metrics and by the expectation that the brand's legacy would sustain itself.

Nike experienced a loss of signal because the system didn't capture the friction points and couldn't process what was starting to go wrong.

Even the most advanced systems can’t detect what they’re not built to see. When signals are weak, fragmented, or outside the data stream entirely, no amount of processing will surface them.

Without a deliberate choice to stay connected to the ground, organizations risk being blind to change until it’s too late.

And that’s how true understanding slips away

Loss of Judgment: When Humans Stop Thinking

This third trap doesn’t begin with blind spots in the data (Loss of Context), or with weak signals automated system fail to detect (Loss of Signal). It begins with a human choice: the decision not to question.

The data is there. The dashboards are working. The humans are in the loop. But the thinking - the active, interpretive, discerning work of judgment - is no longer happening.

This is Loss of Judgment: A cognitive trap where people stop challenging machine outputs, simply because it feels faster, easier, and safer to go along.

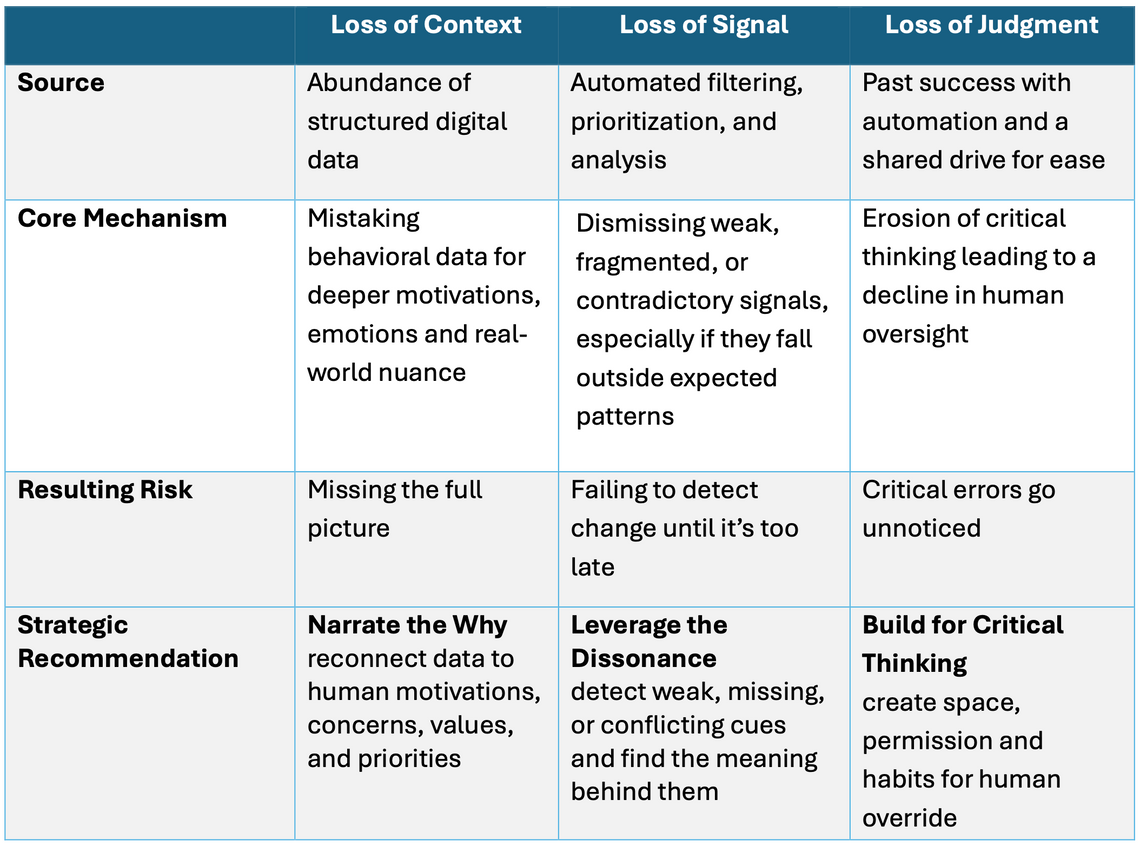

At the core of this trap lies a well-documented tendency known as automation bias. It refers to the human preference for trusting machines, even when their output doesn’t fully fit with what we know or sense.

First described in critical decision environments like aviation and medicine (Mosier & Skitka, 1996), automation bias has since been observed across industriesIn one study, trained pilots working with automated systems were more likely to miss important events when the system didn’t flag them. They also tended to follow incorrect recommendations, even when other evidence pointed elsewhere. Those pilots without automation stayed more engaged and were better at detecting when something was wrong.

This isn’t just a psychological curiosity. As technology becomes more advanced and systems become more accurate, especially in routine ongoing scenarios, trust in them naturally grows. The machines seem to get it right. Their outputs are fast and consistent. And most importantly, they’re usually correct.

We are also drawn to machines because they reduce effort. They spare us the need to weigh options, analyze contradictions, or navigate ambiguity. Simply put, it is so much easier to let the automated system decide. As Parasuraman and Manzey (2010) describe, it's a cognitive shortcut - a way to minimize mental load, especially under time pressure or information overload, so common in corporate settings.

The combination of successful results and the universal desire for mental and psychological ease, makes it harder to slow the process down by asking questions, raising concerns, or pushing back.

And in business environments that naturally reward speed and decisiveness, these outputs, perceived as objective and experienced as effortless, often carry more weight than human input. Over time, teams have less incentive to ask about the hidden costs, and they gradually stop looking for what the model might have missed.

The result is a slow erosion of human discernment, a process known as deskilling. People stop analyzing deeply and rely on suggested answers. They slowly lose the skills they once used to navigate complexity - critical thinking, cognitive flexibility, and independent oversight.

Figure 3 - Automation Bias Loop

Figure 3 - Automation Bias Loop

This trap, too, was evident in Israel’s intelligence failure.

Surveillance teams stationed near the border, who had developed deep familiarity with daily routines on the other side noticed unusual movements, and suspicious shifts in behavior. Junior analysts, fluent in local language and culture, flagged subtle cultural cues and signs of deception. Their insights didn’t come from structured data. They came from immersion, interpretation, and instinct.

However, their concerns contradicted the low-risk assessments of the models, and as a result were acknowledged but not prioritized. In an organization designed to value efficiency, internal alignment, and operational clarity, these human warnings weren’t considered urgent or definitive enough to act on.

Therefore, the issue wasn’t only what the system failed to see; it was how little weight was given to what humans knew.

The loss of judgment was even more pronounced when one of the intelligence’s key technological systems went offline.

As far as is known, no effort was made to construct a threat assessment from alternative sources.

Analysts, accustomed to fast, direct, reliable outputs, didn’t revert to independent integration and interpretation.

The once-routine human skills for doing so had eroded, or no longer came to mind as a viable path.

This dynamic plays out in business, too.

Consider a team using marketing automation to increase sales.

If the model appears successful, meaning conversion rates are higher, no one feels the need to challenge it. After all, why question an automated process that seems to be working. Yet the downsides tend to show up in places the system doesn’t track, including scattered complaints, qualitative feedback, or statistical outliers such as:

customers alienated by off-target offers

opportunities missed with nonconforming segments

overuse of special offers and discounts

Still, because the journey is seen as optimized, revisiting it feels unnecessary or even like a waste of time. And when no one asks, no one sees.

Eventually, the question isn’t whether the model missed something - it’s whether anyone still remembers how to check.

And that’s how habit and ease slowly overshadow true understanding - until it disappears.

Avoiding Data Morgana – How to Overcome the Illusion of Understanding

As digital information becomes more abundant, so does the risk of assuming that everything is already understood.

What’s missing isn’t information, but depth, contradiction, and challenge.

While much of the focus is placed nowadays on improving the machines, this section turns the spotlight back to the human element.

This isn’t about resisting technology or slowing innovation. On the contrary, to truly unlock the promise of intelligent tools, we need to design both the models and the human roles around them.

That means integrating the unique strengths of human thinking where they’re most needed inside the decision-making process.

Overcoming the Loss of Context – Narrate the Why

Data can tell us what happened - not necessarily what it means. Too often, numbers are stripped of the story behind them. And when meaning disappears, so does relevance, leaving us with information without real insight.

To restore true understanding, we need to keep the human lens alive. That means reconnecting the numbers to the motivations, concerns, values, and priorities behind them:

▪ Treat every data point as part of a larger frame - ask what story it tells in people’s terms: goals, doubts, emotional drivers, and social trends.

▪ Include “why checkpoints” in your workflow - moments where people are deliberately prompted to explore the reasons behind the pattern, not just describe it.

▪ Combine quantitative output with qualitative input from people who understand the culture, the dynamics, and the field, because that’s how insights emerge.

To truly understand human behavior - and to act wisely on it - we need both scale and nuance. The digital layer must be grounded in human context, not replace it.

Overcoming the Loss of Signal – Leverage the Dissonance

Most automated systems are designed to recognize repetition - not disruption or contradiction.

However, in complex environments, real insights frequently hide in the gaps: in anomalies, absences, or unresolved tensions. What seems inconsistent or out of pattern could be where the valuable insight lies.

Avoiding this blind spot means leveraging the dissonance and noticing not only what’s there, but what’s missing from the stream, conflicting, or out of place:

▪Pay close attention to anomalies and outliers. What doesn’t fit may be what matters most.

▪Compare signals across sources, behaviors, or expectations to identify inconsistencies - and make sure you understand what they reveal and why they matter.

▪Involve people with specific expertise or cross-disciplinary knowledge from different domains or layers of the organization. They are the ones most likely to spot patterns that don’t align and connect the dots.

Detecting what truly matters begins with embracing dissonance - not ignoring it.

Overcoming the Loss of Judgment – Build for Critical Thinking

Loss of judgment happens through default acceptance, mental shortcuts, and the gradual erosion of our unique ability to interpret complexity.

To prevent this slide, we need to intentionally build for critical thinking - creating space, permission and incentives to pause, reflect, and dispute:

▪ Create opportunities for dissent.

Build defined stages into decision-making where people are not only allowed but expected to offer alternative interpretations.

▪ Reward reflection, not just speed.

Shift the value system to recognize thoughtful challenges as a form of performance, not resistance.

▪ Educate for independent evaluation.

Invest in rebuilding the ability to navigate ambiguity, recognize what might be overlooked, and know when it’s better to hold off on making a decision.

▪ Protect human override.

Make sure every automated system includes a recommended path for human override - especially when uncertainty, subtle indications, or contradictions appear.

Critical thinking is not a given. It’s a skill that can fade if we don’t practice it.

The Path to Smarter Decisions

Ultimately, humans and machines excel at different things.

Machines bring speed, consistency, and scale, but humans bring context, intuition, emotion, and discernment.

To avoid Data Morgana and truly benefit from technological progress, we don’t need to slow down - we need to design for synergy; a partnership where humans and machines each contribute their unique strengths and real-world value.

That’s how we find meaning, detect relevant signals, exercise sound judgment and achieve true understanding.

Principles for Overcoming the Three Traps Behind Data Morgana

Table 3: From Illusion to Action

Table 3: From Illusion to Action

References

Academic

Mosier, K. L., & Skitka, L. J. (1996). Human decision makers and automated decision aids: Made for each other? In R. Parasuraman & M.Mouloua (Eds.), Automation and Human Performance: Theory and Applications (pp. 201–220). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Parasuraman, R., & Manzey, D. H. (2010). Complacency and bias in human use of automation: An attentional integration. Human Factors, 52(3), 381–410

Rozenblit, L., & Keil, F. (2002). The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth. Cognitive Science, 26(5), 521–562

Netflix Case Study

Welch, C. (The Verge, Apr 19 2022). Netflix just lost subscribers for the first time in over a decade - 200,000 in Q1, forecasted up to 2M in Q2

McCluskey, M. (TIME, Jul 20 2022). Netflix loses nearly 1 million subscribers in Q2 2022 - wiping out 65% of its 2022 market cap

Netflix. (2022, April 19). Letter to Shareholders – Form 8-K. “COVID clouded the picture by significantly increasing our growth in 2020…”

Nike Case Study

Modern Retail. (2023). Nike posts its first digital decline in nine years - includes digital sales drop of 3% and net income fall of 16%

Forbes. (2024). Nike stock tanks to 4-year low amid brand struggles - shows share price decline from $167 in 2021 to about half by end-2024

Gali Hershenzon

Founder at SapioGali established Sapio Research and Development Ltd. in 2007 and has managed the company ever since.

Gali holds a BA in Psychology and Business Administration from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and an MBA from Tel Aviv University.

Gali is a marketing specialist with over 15 years of accumulated experience in market research, together with branding and marketing strategy. Her extensive experience managing quantitative and qualitative research projects enables her to achieve innovative consumer insights and resolve complex marketing issues.

Gali previously lectured on marketing and statistics at various academic institutions, and is currently a guest lecturer for MBA students at Tel Aviv University's School of Management.