Marketers seduced by generational glasses: Part 2

Does your year of birth really hold the key to your buying habits and to how you approach your work? Many marketers are adamant that it does, and the results of their work back it up.

Does your year of birth really hold the key to your buying habits and to how you approach your work? Many marketers are adamant that it does, and the results of their work back it up.

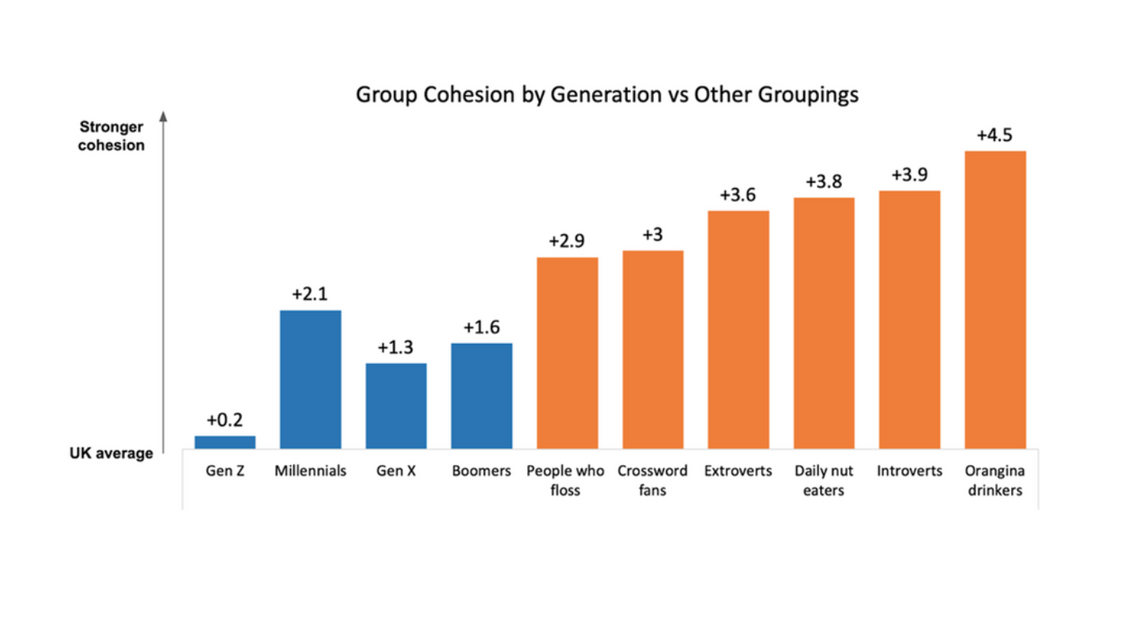

However, some studies have found that Orangina drinkers or introverts of different ages have more in common with one another than people from the same generation. And over a two-part article, we’ll unpack this in more detail.

In part 1, we looked at the harm generation labels cause, and how old brands vie for new audiences. But now it’s time to answer the big question. Do people change with age?

Do people change with age?

The early years of this decade saw more critical approaches to the meaning accorded to generational cohorts. I

2021 saw the publication of the book Generation Myth, in which sociologist Bobby Duffy says that the notion of generational cohorts can be helpful in understanding certain phenomena but not as much as it has come to be believed. In addition to the question of generations, he discusses the historical context and different life stages, i.e. how people tend to change as they age.

His overall conclusion arrived at through the analysis of a vast amount of data, is that people from distinct age groups are far more alike than is generally thought and that the generational perspective is promoted by a whole new sector that has developed around it.

Duffy claims that 10 years ago US companies spent $70 million on generational consulting in the context of workforce. However, there are no proven workplace-related differences across generations. He also notes that there is no evidence supporting the claim that higher suicide rates or lower sexual activity are limited to young people. These tendencies have been observed across the entire population in both the US and UK.

BBH Labs’s analyses made an even bigger splash. The organization created a similarity index based on the UK’s 2019 TGI (Target Group Index) data about the products and services bought by consumers and the media they use. Following its publication, many marketing media carried headlines saying that average nut eaters have far more in common with each other than the members of the Z Gen.

I often observed how passions and habits affect similarities within groups when examining communities as part of my nethnographic research. I noticed fatigue with having to be constantly present on social media and compete with others by posting appealing photographs and with a dependence on online interactions.

-- H. Guild, ‟Puncturing the Paradox: Group Cohesion and the Generational Myth”.

| source

-- H. Guild, ‟Puncturing the Paradox: Group Cohesion and the Generational Myth”.

| source

The opposite of the more familiar FOMO (fear of missing out), the JOMO (joy of missing out) is the joy derived from disengagement but it does not preclude digital activities. Surprisingly enough, JOMO can work well online for those who play vintage games without chasing newly released titles or engaging in social media activities that are a throwback to the good old forums: anonymous, topic-focused, fostering passions or reflection. Such communities can function brilliantly across generations. Their members avoid discussing generational pigeonholing and bonds through shared interests or life experiences.

On lenses and glasses: a new way of looking at things

Noticing ever more gaps in the functioning of cohorts, even the companies that pioneered generational research and ran numerous generation-related workshops and studies have begun reconsidering their approach.

Last year, the Pew Research Center pointed out that it had spawned a whole new sector serving up clickbait or marketing mythology on generational segments.

The Center announced it would no longer do generational analysis without historical data allowing it to compare generations at similar stages of life, and it would consider additional environmental factors (beyond age) to make generational comparisons. Its intention is to use lenses that are better suited for studying specific issues without rigidly adhering to generational labels that are known to have led to oversimplification and stereotyping.

We look at the world through certain glasses that affect our perceptions. Anthropologist Franz Boas coined the term ‟cultural glasses” to refer to the fact that no one perceives reality as it is, or in the same way as others. We tend to consider some ways of seeing the world as prejudiced and to overlook the fact that our own outlook can get distorted by our cultural glasses.

Many marketers have come to believe that their target groups are wearing generational glasses rather than cultural ones or that the segments tagged with different letters can be seen as monoliths. The truth, however, is that the generational glasses are now firmly planted on the noses of the marketers themselves. Over time, they have ceased to be noticed, leading to misleading observations and conclusions that can inform wrong business decisions.

So, what can we do? The reasonable thing to do would be to shed the generational glasses and look at the particular groups with more curiosity and reflection without over-isolating them from the rest of society or accentuating the differences which on closer inspection often prove to be illusory.

Marek Tobota

Owner at Data TribeFounder of Data Tribe - a Warsaw based strategy and research boutique. Netnographer and trendspotter with wide experience in marketing and PR. Seeker for new ways of qualitative research in the Internet.