Marketers seduced by generational glasses: Part 1

Does your year of your birth really hold the key to your buying habits and to how you approach your work? Many marketers are adamant that it does, and the results of their work back it up.

Does your year of your birth really hold the key to your buying habits and to how you approach your work? Many marketers are adamant that it does, and the results of their work back it up.

However, some studies have found that Orangina drinkers or introverts of different ages have more in common with one another than people from the same generation. And over a two-part article, we’ll unpack this in more detail.

The notion of generational cohort was first introduced as a sociological tool for tracking social change and intergenerational dynamics. Over time, it has became entrenched in popular culture turning into its own caricature, brought down to a hunt for differences across generations.

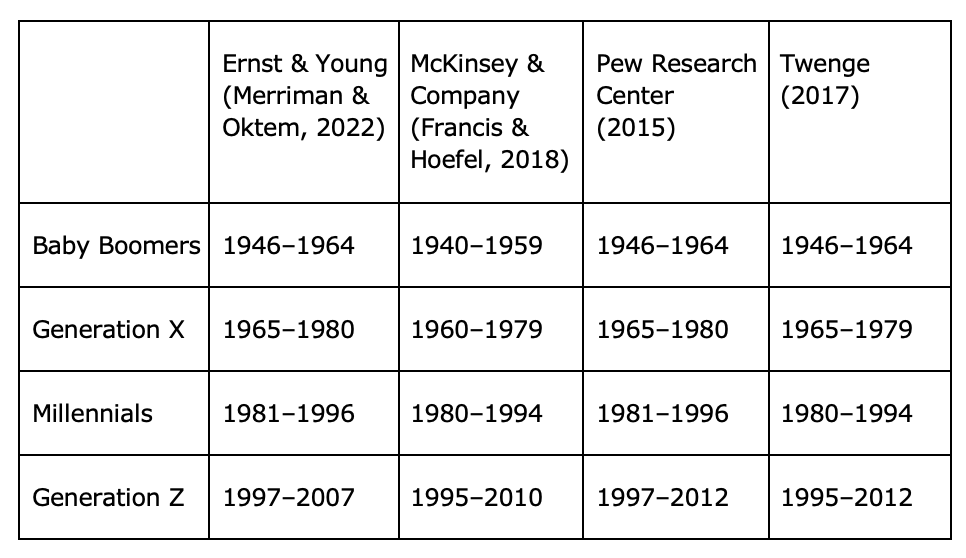

Notably, research on generational cohorts hasn’t produced a set of uncontested definitions. Different studies introduce different names and timelines. Some even posit more generational groups than others. The way generations are defined by difference businesses is inconsistent too:

-- A.J. Clements, ‟A Critical Review of Research on Generational Cohorts”

| source

-- A.J. Clements, ‟A Critical Review of Research on Generational Cohorts”

| source

A decade back or so, Poland was gripped fascinated with Gen Y (millenials). Millennials made marketers, want their brands to be young, fresh, and in synch with the current trends and new consumer tastes. The media was awash with titles screaming Gen Y. We witnessed warnings of doom looming on the horizon due to ever-worsening productivity and the millennials’ entitled mindset combined with hopes for humanity’s salvation owing to the millennials’ pro-eco attitudes and other ideas popular among them. Gradually, this type of simplification seeped into brand communications, becoming more of a cultural code than actual data-based findings.

Can generational generalization be harmful?

As the focus shifted onto the letter Z, things became bumpier. But never fear, you can always start all over again. Enter the Alpha generation.

The Alphas turned 13 last year according to one timeline. This is the age when one is allowed to set up profiles on places like TikTok or Facebook.

More likely than not, many brands have a communication strategy ready for the occasion, often using TikTok and Facebook to attract the new kids on the social media block. So, brace yourself for another barrage of generational generalization. Except that for the first time in history, a generational cohort will be growing up amid noisy messages telling them who they are.

But I believe there are dangers in segmenting people by age and telling them who they are. Numerous psychological studies have shown that communication generalizations can cause harm to young people.

The talk about how generations can adversely affect individuals. A series of studies led by Joshua Grubbs showed that adolescents and young adults are aware of the media portraying them as privileged and narcissistic and many of them believed that the portrayal was accurate. This only exacerbated the stereotypes that had always stemmed from the friction between children, their parents and grandparents. And I don’t mean the familiar ‟those were the days” here, but the constant labeling.

Do ‟old” brands find it easy to vie for young audiences?

All brands with a long history struggle to retain a fresh feel and to appeal to younger buyers. These brands take steps to avoid being labeled as ‟OK, boomer”. A label that inevitably leads to being dismissed as irrelevant.

Many marketing campaigns have been designed to elude this trap. Notable American examples include ‟Not Your Father’s Oldsmobile” (1988) or, much more recently, ‟Not Yours Mother’s Tiffany” (2021).

In the late 1980s, Oldsmobile badly wanted to shake off its image as a maker of dull cars for senior citizens, leading to one of the most bizarre advertising campaigns launched by a Detroit car maker. The idea was to film spots with a handful of celebrity has-beens and their children, who were not household names at the time.

The idea itself wasn’t a bad one. But the execution alienated all possible audiences, leaving the brand users embarrassed while the young audience found the message as convincing as Steve Buscemi’s character’s words to high school students ‟How do you do, fellow kids?” that found their way into a famous meme. Years later, some credited the campaign with hastening the company’s demise.

The former fame of the parents appearing in the spots turned out to be irrelevant. This may provide a case for those who argue that generational analysis is about ensuring relevancy. ‟Not Your Mother’s Tiffany”, the more recent of the two campaigns referenced above, relies heavily on reports on what young women find fashionable and relevant. And it sends a rebellious message to boot.

The campaign posters omitted mothers and featured only daughters but both the posters and the social media content soon came under fire. The brand’s loyal customers felt offended with many young people joining the chorus of critical voices. Responses like Leave my mother out of this!!!‟ were seen scribbled on the posters. Some claimed that the content was created in a calculated move to generate hype. But many experts voiced harsh criticism, pointing out that the message was ‟against” something, focusing on generational conflict rather than supporting something or building relationships underpinned by shared beliefs.

The ads were an attempt to capture a certain age-old societal tension. The question is how this relates to the enduring constructs of generational cohorts, which, increasingly often, are defined in isolation from the life stage of the people in question. Is this all just the question of the friction between the young and the old?

We’ll look into this in part 2.