Encouraging healthy behaviours: Three key psychological considerations

With NHS waiting lists near record highs, there is a strong case for encouraging preventive behaviours like improved diet and exercise. However, there are three psychological reasons why engaging the public in such behaviours is extremely challenging.

In May this year I had the pleasure of being a panellist at a day-long event about prevention in healthcare, hosted by The Adelphi Group.

With a potential almost 10 million people on NHS waiting lists in the UK, a greater focus on preventive behaviours like diet and exercise can help tackle the ever-growing challenge of healthcare demand.

However, achieving engagement is much more challenging in a prevention context than in a treatment context.

This article draws out three key psychological considerations when it comes to engaging the public in preventive health behaviours:

1. The future is not the present

2. Our reactions to uncertainty are uncertain

3. Humans are emotional beings

Let’s begin with the first consideration…

1. The future is not the present

A cognitive bias is defined in behavioural economics as a “systematic error in human decision making”.

Cognitive biases describe a wide variety of ways in which humans don’t always do what they “should”, and behavioural economists have to date uncovered almost 200 cognitive biases.

One such bias is present bias. This describes how humans naturally focus on the here and now, and are typically less motivated by what may happen in the future.

Present bias therefore causes a big challenge when it comes to encouraging preventive health behaviours.

In short, when compared to telling people about health risks in the present, telling them about such risks in the future simply may not be very impactful.

So should we give up on trying to encourage preventive health behaviours?

No…but in light of the present bias we need to think carefully about our approach.

For example, studies trying to encourage people to contribute more into pensions (a classic present vs future challenge) have found that showing an AI-generated picture of them when they’re much older can concentrate the mind and increase payments in the present.

Alternatively, reminding folks of good things they’ve done in the past can also increase the likelihood of such happening again in the future, as this study of physical activity levels of adults with Type 2 Diabetes found.

2. Our reactions to uncertainty are uncertain

The second key psychological consideration when it comes to encouraging preventive health behaviours is that humans do not respond predictably to uncertainty.

In behavioural economics speak this is due to ambiguity aversion – which describes how humans usually prefer certainty to uncertainty.

For example, when presented with information about a potential health risk, some people will disengage entirely – exhibiting an over-confidence that any possible negative consequences simply won’t happen to them.

On the other hand, others will disengage by burying their heads in the sand due to heightened fear – an effect known in behavioural economics as deliberate ignorance, or the ‘ostrich effect’.

So again, should our efforts to encourage preventive health behaviours be put off?

No. Instead, we should embrace the challenge when developing prevention messages.

These should focus on clear, ambiguous facts we know are true – and avoid injecting uncertainty through informing about factors which only may be related to negative health consequences.

3. Humans are emotional beings

The final key consideration is – as laid out in this excellent book – humans are emotional beings.

Considering human emotions is especially important when thinking about preventive health behaviours like diet and exercise.

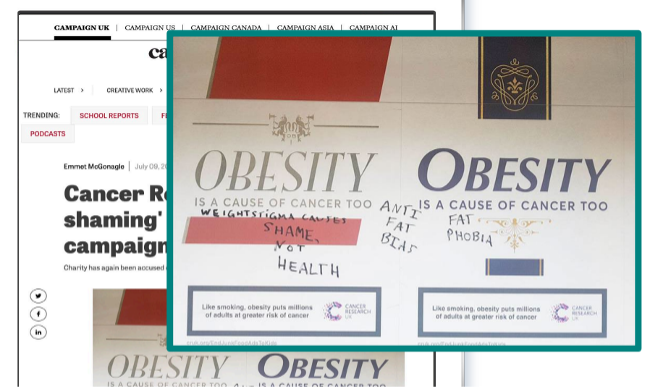

For example, while evidence suggests messages about the potential negative health consequences of doing (or not doing) a preventive behaviour can be successful, these have to be framed carefully. Causing shame or implying blame can trigger negative and counter-productive reactions.

So should we try to avoid emotions altogether?

No. Again there are more subtle approaches.

For example, an alternative approach is to produce communications which induce or raise awareness or expectations of future regret about not performing a preventive health behaviour.

Messages focusing on regret – as opposed to more dangerous emotions – have been shown to boost motivation for preventive health behaviours, as in this study which increased cervical screening uptake.

Conclusion

This article has presented three key psychological considerations when it comes to engaging the public in preventive health behaviours:

1. The future is not the present

2. Our reactions to uncertainty are uncertain

3. Humans are emotional beings

To learn more about behaviour change – and in particular four useful frameworks and models – please request our free guide here.

Alternatively, for more succinct behavioural science ‘bytes’ sign up to our free monthly newsletter.

Chris Harvey

Founder at Activate ResearchChris Harvey is the Founder of Activate Research. He is an expert in helping research agencies add complementary insights from behavioural science (and psychology more broadly) to their research offer, enabling end clients to better understand, predict and influence target audience behaviour. Chris has over 10 years’ experience in the research industry, working for agencies including Dunnhumby, GfK and YouGov, and in 2016 achieved a Distinction in MSc Behavioural Science.