B2B is no less prone to psychological forces but they are better at disguising it

B2B decision-making is seen as more rational than B2C, leading to less emphasis on behavioral science and psychological influences like gut feelings and instincts.

It’s assumed that decision making in professional sectors is more rational and considered than within consumer sectors. Perhaps this is why behavioural science has less traction in B2B marketing than it does B2C.

This means that often when researching B2B, we often don’t measure the psychological influences on behaviour like gut feeling, instinct and rules of thumb

However, I’d argue that decisions within professional services are equally prone to these kinds of psychological influences. But just a different set than what we see in consumer markets. This is down to distinct but equally interesting dynamics and incentives which exist in B2B.

The key difference between decision-making in professional vs consumer sectors isn’t between being rational and emotional or biased and unbiased. It’s due to the types of influences on our decisions. Once we understand the real influences, incentives and dynamics at play in professional circumstances we see a different picture to the image of the rational emotionless business professional.

Defensive decision-making

A key distinction between consumers and professionals is around defensive decision-making. Defensive decision-making entails choosing an option which protects yourself and your own position within the company despite being sub optimal for the organisation.

This is because often consumers only have to worry about consequences for individuals. But an individual within an organisation, must consider the needs of both the organisation and themselves. When the two conflict, business professionals will often choose to opt for what is in their own interest rather than in the interest of the wider organisation. The Max Planck Institute for Human Development did a study on this phenomenon surveying 950 managers from all hierarchy levels of organizations. Around 80% of respondents reported that at least one of the ten most important decisions they had made in the past 12 months had been defensive.[i]

Risk Aversion

The fear of blame or negative consequences drives many decisions, favouring solutions that seem safe. Understanding the incentives in place for a professional decision-maker are crucial for understanding their behaviour. In this case it could mean for example sticking to known brands or established processes, even if new options might offer better value. Simply, because it would be much easier to blame someone for choosing a new brand or process than an established one. If they are simply following established practice, they have a get out of jail clause they can turn to if something were to go wrong.

When speaking with professional decision-makers, their incentives often surface even before the specific topic is discussed. This is why it is crucial to understand the psychological influences and dynamics at play at the beginning of any research discussion.

If research only considers the stated needs — for example, “how do I get the best service for my company” — and ignores the underlying personal needs — such as “how do I look competent” or “how do I protect my job” — then the analysis will miss the real drivers of behaviour. Recognizing both levels of need is essential to truly understand the challenges decision-makers face.

Social proof and group dynamics

The philosopher Nietzsche once remarked about the differences between understanding someone as an individual versus within the context of a group that:

Insanity in individuals is something rare — but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs, it is the rule.” [ii]

It’s extreme to suggest that the behaviour of those within a work team or organisation is insane. But it’s fair to say that being ‘in a group’ changes behaviour, often in ways which would seem ‘irrational’ to an individual decision-maker.

Within a professional context, decisions are rarely made by an individual. But instead, by committees or groups. For business professionals procuring a new product or service isn’t just about the product’s features. But rather how those product features can aid the group dynamic, building credibility, trust, and reassurance across it.

We see that enthusiasm expressed by one person in an organization doesn’t always lead to rapid adoption. It must be matched with group advocacy. Individual enthusiasm and group advocacy often overlap, but they’re not always aligned, and failing to account for that gap can stall uptake.

Objectivity trap

Although psychological forces are no less present in B2B, there’s a greater illusion around them and more effort goes into hiding them.

Think about how procurement evaluates new suppliers. supplier. They have to follow a process and a structure. They can’t be seen to base decisions on a feeling, that would seem too reckless, unserious and unstructured. A new supplier for example, may be given a score on certain metrics, say for example 20 on expertise, 20 on scalability and 10 on strategic vision.

As such, we are meant to believe that this evaluation is purely a mathematical exercise of adding up different scores. However, when we investigate how decisions are made, we see a different story. The frequent retaining of a long-term supplier despite throwing out briefs to multiple supplier, the trust in a large supplier purely because of the power of their name or even the power of personal connections which gives someone a foot in the door. Often, what they really did is they made an emotional decision on which agency they’d like to work with. And they retrofitted the numbers to get the result they wanted. Even if the actual decision does not come from a structured process, it has to look like it does.

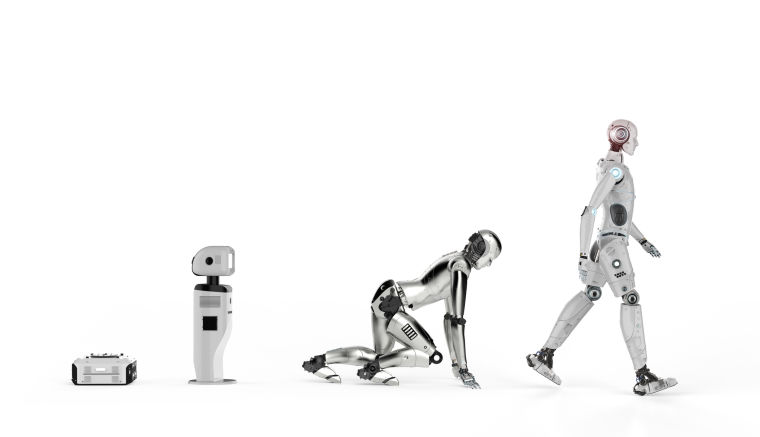

Much of B2B activity operates this way. Business professionals themselves like to hold up this image the emotionless, rational decision maker. Numbers, charts, and reports are often produced less to generate real insight and more to justify decisions. The goal is not always to find the best answer but to demonstrate a rational process. This creates a wide gap between the appearance of business rationality and the messy, human reality it conceals.

Within large corporations in particular, there is established reputation, brand and structure to protect. They are often accountable to shareholders, regulators or the public. If you have clearly made a decision which hasn’t followed structured protocol it would risk undermining confidence both internally or externally. Imagine Coca cola doing a rebrand away from the iconic red packaging because someone internally prefers the colour green. If it goes wrong, the decision-maker has no internal research to point to justify this decision. Decisions must appear rational, systematic, and heavily supported by data and logic. Yet appearance should not be mistaken for reality. B2B decision-makers won’t admit that choices are driven by intuition, personal feelings, or even self-protection but it doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen.

This is not to say the practice of relying on intuition is inherently negative. Spreadsheets and metrics will never fully capture the role of emotions, relationships, and trust, all of which remain central to business decision-making.

Conclusion

The idea that B2B decisions are m rational is more myth than reality. Beneath the surface of spreadsheets, scorecards, and procurement protocols lie a whole set of dynamics, heuristics, emotional drivers and psychological incentives albeit a different set to what we see in the consumer world. Defensive decision-making, the illusion of objectivity, and the power of social dynamics are all examples of professionals demonstrating that they are no less human when they step into an office.

For researchers looking to understand the world of B2B, the challenge is not to strip emotion out of the process, but to recognise and work with it. This where an understanding of behavioural science principles can enhance B2B research.

This can look like more work upfront to understand the specific context and dynamics at play before research discussions, actively testing for emotional incentives and intuitive reasoning in surveys, and, for those shaping recommendations, speaking directly to the human side of decision-makers. Decision-makers within organisation have to grapple with team dynamics, make defensive choices to protect themselves and their careers, and constantly balance risk aversion. By recognizing the reality of B2B rather than the appearance of B2B, research can deliver insights that resonate more deeply with individuals within organisations.

[i] Artinger, F. M., Artinger, S., & Gigerenzer, G. (2019). "C. Y. A.: Frequency and causes of defensive decisions in public administration." Business Research, 12(1), 9–25. doi:10.1007/s40685-018-0074-2

[ii] Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. Translated by Helen Zimmern, Section 156 (original German publication 1886).