Winners and losers in the game of AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders' Part 1

In this two-part article, the authors will lay out a ‘plausible possible future’ for knowledge work, with a framework that provides a view of the potential impact of the widespread adoption of AI on the knowledge worker.

Article series

AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders'

- Winners and losers in the game of AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders' Part 1

- Winners and losers in the game of AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders' Part 2

In this two-part article, the authors will lay out a ‘plausible possible future’ for knowledge work, with a framework that provides a view of the potential impact of the widespread adoption of AI on the knowledge worker.

We know that AI is creating new jobs, and we can see all the exciting opportunities arising. But there is a strong possibility AI will massively disrupt ‘knowledge work’. As authors, we don’t have a crystal ball, but we do believe that a strategic conversation should be fostered - supported by effective scenario planning – to better understand some of the bigger picture implications of AI rather than putting it in the ‘too-difficult’ box.

The term ‘Knowledge Worker’ was coined by management theorist Peter Druker in The Effective Executive as far back as 1966. However, he introduced the concept of ‘Knowledge Work’ a few years earlier in his book, The Landmarks of Tomorrow. While ‘Knowledge Work’ has been difficult to define over the years, in trying to categorise it, we can rely on the adage that ‘we know it when we see it’. At the end of the twentieth century, Druker observed that "the most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution, whether business or non-business, will be its knowledge workers and their productivity." He hadn’t foreseen the rise of artificial intelligence and its likely impact on ‘knowledge work’ and the ‘knowledge worker’.

So, who are these knowledge workers? Definitions are many and varied, but we would say that they are individuals who allocate knowledge to productive use. They have specialised knowledge on a specific topic or have the ability to find or access new information and then the capability to analyse and utilise that information to generate actionable knowledge. They are performing roles in the knowledge economy, including anticipatory imagination, problem-solving, problem-seeking, and generating ideas and aesthetic sensibilities (Loo, 2017). We find them in market research to copywriting, from advertising to management consulting, from software development to the law, from accounting to architecture.

The authors have spent their entire careers as knowledge workers enabled by an era of exciting technological change - the 1980s to the 2020s. However, the tide of technological change has suddenly and rapidly risen to new heights with the roll-out of widely available artificial intelligence. The nature of this change has shifted AI from enabler to substitute such that it is now threatening to deluge knowledge work and the knowledge worker.

With so much turbulence on so many fronts, it’s tempting to put a serious review of the longer-term strategic implications of AI on the back burner, kicking the can down the road until it is somebody else’s problem. This would be a mistake.

I can't think about that right now. If I do, I'll go crazy. I'll think about that tomorrow”

Scarlet O’Hara, ‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939)

We need action now to address the implications of AI and embed the new skills we will need to develop going forward, as well as consider how we will manage wealth distribution and maintain stability within our society.

The writing is on the wall

The picture is building on how AI is likely to transform our lives. The majority view is that the impact of AI will be significant and sustained.

I’ve always thought of A.I. as the most profound technology humanity is working on—more profound than fire or electricity”

Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai, April 2023

But within this, we find both utopian and dystopian perspectives.

Through the positive lens, we have a recent Goldman and Sachs study suggesting that global ten-year GDP will rise by 7% due to the economic gains anticipated from AI and that their "expectation is that generative AI will have a measurable macroeconomic impact." The study also anticipated a lift in US productivity of 1.5% if widespread adoption was achieved over the next ten years. In parallel, McKinsey researchers reported that “generative AI’s impact on productivity could add between $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion annually to the global economy.”[1]

Generative AI could enable labour growth of 0.1 to 0.6 per cent annually through 2040, depending on the rate of technology adoption and redeployment of worker time into other activities. Combining generative AI with all other technologies, work automation could add 0.2 to 3.3 percentage points annually to productivity growth.”

McKinsey

Economist and London Business School Professor Michael Jacobides goes further – he cites research suggesting a 25% to 80% increase in productivity, which he contrasts to the 25% productivity boost attributable to the steam engine.

In contrast, the dystopian vision of the future offers us algorithmic bias, misinformation and widespread job displacement, with the societal polarisation and unrest that might stem from this. There are projections that 80% of the US workforce will see at least 10% of their role being taken over by AI, with some reports suggesting that 20% of the workforce will have half of their job substituted by artificial intelligence[2].

The same Goldman Sachs economists estimated that AI “could ultimately automate roughly 25% of work tasks” in major developed markets like the U.S., and greater automation will "drive labour cost savings”[3]. Famed venture capitalist and major OpenAI investor Vinod Khosla goes further. He believes 80% of work functions that compromise 80% of economically valuable jobs will be able to be done by AI.

There’s no economic law that says that when technology advances everybody necessarily benefits. Some people, even a majority of people, could be made worse off.”

Erik Brynjolfsson (Professor and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-centered AI)

The authors’ own research suggests that, against this backdrop of positive and negative AI messages, the arrival of AI is such a massive event that people and businesses are finding it difficult to understand its impact. It is outside their frame of reference, and many experience ‘perceptual blindness’, with responses tending to fall into two camps.

Let’s bury our heads in the sand, and we will worry about that tomorrow … taking a ‘play it by ear’ approach to tactical and strategic change.

Let’s take some limited action because we can see how an aspect of AI can be comparatively easily added to improve something we currently do, e.g. acquire creative prompt engineering skills to help generate faster ad copy.

This begs the question: how should we best consider the broader implications of AI in the knowledge workplace – what is the basis for this discussion?

A new social model

As market and social researchers, the authors have used many models of social stratification in their work based on socioeconomic factors such as income, education, occupation and location. Knowledge workers have populated the top levels of all of these socio-economic models.

In more recent years, there has been much discussion as to whether ‘social class’ as a construct is now dead – we are now all bourgeois, burger lich, or de la clase media, salaried rather than paid a weekly wage, in a one-size-fits-all social homogeny. But the arrival of AI now raises the issue of whether this powerful new technology is creating new social strata – strata in which occupation and education no longer open doors to the highest levels of society.

So, in this two-part article, we will outline a scenario of how things might look in five years’ time in order to trigger some serious strategic thinking about how to structure the labour market and create a fair society.

And here, it is worth noting that this is not a prediction. We are mindful of the fact that US economist Edgar Fiedler once noted that “He who lives by the crystal ball soon learns to eat ground glass!”. And he is not wrong – so we are not in the business of making predictions. We align with Nobel Laureate Niels Bohr, who said, “Predicting, particularly when it is about the future, is difficult”. But that does not mean that we are without tools that allow us to prepare for what is to come. The question we face is: can we imagine different AI futures so that we may evolve to meet these scenarios, or do we simply wait and react to what comes along and hope for the best?

The authors, as experienced scenario planners, favour anticipating different futures and planning accordingly. So, we have set up a ‘strawman’ that is intended to provoke a dialogue about the labour market, workforce planning, and organisational design in the AI-shaped workplace.

Our approach is deliberately designed to be thought-provoking: it is aimed at prompting a discussion and ensuring that our business leaders and decision-makers don’t put planning for the AI workplace into the ‘too difficult’ box but start planning for it now. By creating a ‘strawman’ – an idea to be knocked down - we can trigger a debate about what action we need to start taking now.

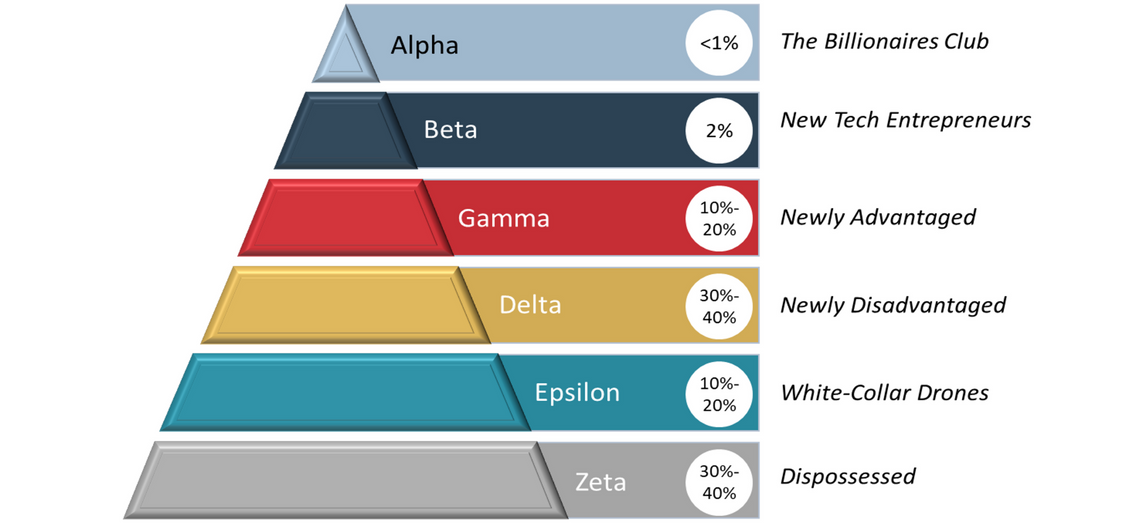

We borrowed from Aldous Huxley to paint the picture of who is likely to be the winners and losers as capital replaces labour and AI becomes a substitute for human skills. In his 1932 novel Brave New World, Aldous Huxley sets his story in a futuristic World State where consumerism has replaced religion, science has eliminated illness and ageing, and the happiness of all is ensured by genetic engineering brainwashing, recreational sex and tranquillising drugs. Citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy. Eugenics and indoctrination have engineered citizens into predetermined castes … Alphas, Betas, Gammas, Deltas and Epsilons.

We have co-opted Huxley’s strata of Alphas, Betas, Gammas, Deltas and Epsilons to suggest a new workplace - and, by implication, societal – dynamic. Our framework has six levels based on people’s ability to harness or adapt to AI and develop the skills necessary to offer value and differentiation in a knowledge workplace shaped by AI.

So, stay tuned to read the second part of this article to learn more about the Billionaires’ Club, our New Tech Entrepreneurs, the Newly Advantaged, the Newly Disadvantaged, White-collar Drones and the Dispossessed.

[1] McKinsey The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier

[2] GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. Eloundou (OpenAI), Manning (OpenAI), Mishkin (OpenAI) and Rock (University of Pennsylvania) August 22, 2023

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-ai-code-generate-gpt-4/

[3] Goldman Sachs. "Upgrading Our Longer-Run Global Growth Forecasts to Reflect the Impact of Generative AI (Briggs/Kodnani)."

David Smith

Director at DVL Smith LtdDavid Smith is a Director of DVL Smith. He is also a Professor at the University of Hertfordshire Business School. He holds a PhD in Organisational Psychology from the University of London and is a Graduate Member of the British Psychological Society.

He is a former Vice President of ESOMAR and also a former Chairman of the UK Market Research Society (MRS).

He is a Fellow of the Market Research Society, a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Marketing and also a Fellow of the Institute of Consulting. David is a Certified Management Consultant.

Adam Riley

Founding Director at Decision ArchitectsAdam Riley founded insight consultancy Decision Architecture Limited in 2006. His 25-year-plus career has spanned market research agencies, client-side roles and management consultancy. Adam joined TN-AGB in the early nineties, before moving to RSL in its embryonic international research team.

After an MBA at The London Business School, he joined Samsung in South Korea, as a Global Marketing Strategist, before moving back to London and becoming a senior member of the marketing strategy practice of Monitor Company (now part of Deloitte).

Article series

AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders'

- Winners and losers in the game of AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders' Part 1

- Winners and losers in the game of AI-Workplace 'Snakes & Ladders' Part 2