Optimising marketing communications channels using behavioural science

A focus in market research studies is sometimes on understanding customer or prospect optimal communications channels for hearing about a new, or existing, product or service.

Introduction

A focus in market research studies is sometimes on understanding customer or prospect optimal communications channels for hearing about a new or existing product or service. From a behavioural science perspective, this is an especially key consideration given the frequently cited messenger effect. This describes how the source of a message is often much more influential on the recipient resulting behaviour than the actual content of the message.

In terms of how such optimal channels are established, research respondents are most typically asked to name their preferred channels (e.g. in qualitative research) or to assess the extent to which they prefer a number of different potential channels (e.g. in quantitative research). However, what does the question of channel preference actually mean to respondents? Are they thinking about the most accessible channels? Or perhaps the channels they trust most? Further, given the powerful “say-do gap” – the discrepancy between what we say and what we do in practice – is a high general preference for a particular channel any guarantee that communications through this channel will be consumed and acted on?

This article uses a recent research project example to illustrate how behavioural science – and one particular behaviour change model – can help provide deeper insights, in any situation, into communications channels most likely to influence future behaviour.

It first introduces the concept of models and the University College London COM-B model. It then illustrates how this model can help us design clear, simple questions which enable us to best identify the channels through which communications are most likely to be consumed and acted on. While the project example used is quantitative, a similar approach can also be taken in qualitative research.

Behaviour change models

Behaviour change models represent or explain the operation or mechanism of something. This allows us to develop hypotheses about why people are behaving as they are currently. Critically, models also help provide a picture of possible courses of action to help bring about behaviour change. They also help us minimise any incorrect assumptions we may make about behaviour and avoid omitting potentially important factors.

COM-B model

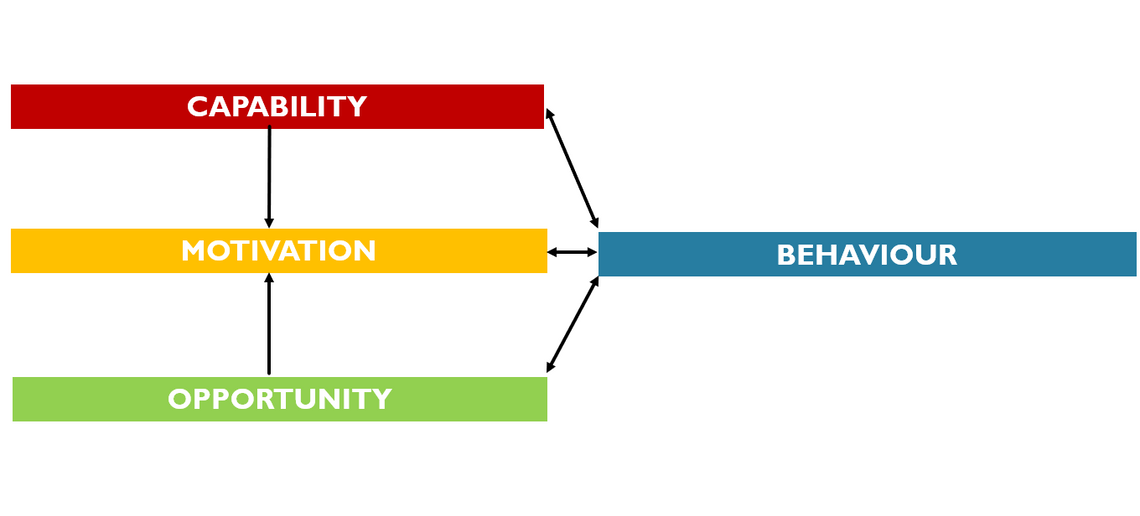

One proven behaviour change model (summarised below) is the University College London-developed COM-B. This synthesises findings from nineteen behaviour change frameworks. In summary, to do a behaviour, someone must have three things: Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation.

First, Capability describes the need for the person or people concerned to have either the physical strength or stamina or the psychological knowledge or skills to perform a behaviour. Opportunity describes the need for a conducive physical and/or social environment. Finally, motivation describes how the person or people must have sufficiently strong motivation, and crucially, at the relevant time.

A recent example: understanding communications channels most likely to influence behaviour

In a recent study, we used the COM-B model to create quantitative survey questions to help understand communications channels most likely to positively affect physicians’ future behaviour towards a new product. Under each of the three COM-B pillars described above, a 7-point agreement scale question was created, which was intended to best encapsulate that pillar.

First, under Capability, physicians were asked to rate how easy they think it is to understand information about relevant products when it comes through a number of different channels. Under Opportunity, respondents were asked to rate their preferences for each channel from an ease of access perspective. Finally, under Motivation, they were asked to rate how much they trust each channel.

Using these three simple questions, the channels where communications would be most likely to positively affect physicians’ future behaviour could be calculated. In particular, these were the channels where physicians had all of the following: the Capability to consume the communications (measured by high ease of understanding), the Opportunity to do so (measured by high ease of access), and the Motivation to do so (measured by high ease of trust).

Results showed that the most effective channel overall was, by some distance, medical websites: 85% of physicians had each of the Capability (high ease of understanding), Opportunity (high ease of access), and Motivation (high ease of trust) to consume relevant information from this channel.

Further, the approach of asking separately about Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (as opposed to simply asking for overall preference) revealed some interesting and actionable findings. For example, while education events were rated very easy to understand (80%) and trust (79%), they were deemed much more difficult to access (66%).

Finally, further analysis demonstrated the key connections between the three COM-B pillars, as predicted by the two one-way arrows in COM-B (see image above). In particular, this helped to describe the process by which high Motivation (trust) is achieved. For example, for the most effective channel (medical websites), high trust was associated with both high ease of understanding and high ease of access.

Conclusion

This article has shown how the COM-B model, when applied in quantitative research, can help provide deeper insights, in any situation, into communications channels most likely to influence future behaviour. While the example above is based on quantitative research, the same approach of requiring high Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation can also be applied in qualitative research.

In addition, the COM-B model can help provide deeper insights into the optimum combination of channels (as opposed to examining different options separately). This is achieved through an advanced quantitative analysis method which will be explored in a future article.

To access any of our 5 free in-depth guides to behavioural science and market research, please visit www.activate-research.com

Chris Harvey

Founder at Activate ResearchChris Harvey is the Founder of Activate Research. He is an expert in helping research agencies add complementary insights from behavioural science (and psychology more broadly) to their research offer, enabling end clients to better understand, predict and influence target audience behaviour. Chris has over 10 years’ experience in the research industry, working for agencies including Dunnhumby, GfK and YouGov, and in 2016 achieved a Distinction in MSc Behavioural Science.