Article series

COVID-19 impact

- Making healthy habits stick after COVID

- Shobservatory Research Chronicles: Lockdowndiaries

- Capturing early stage consumer feedback, post-COVID

- Evolution of physical space in retail and hospitality

- November 2021 COVID-19 forecast & commentary

- Ethical brands in pandemic times

- November 14 reforecast due to OSHA rule stay

- COVID-19 December 2021 forecast for the USA

- Omicron

- COVID-19 forecast in the USA

- COVID-19 update for the USA

- COVID-19 Omicron retrospective

- Crises and community

- Research that makes a difference

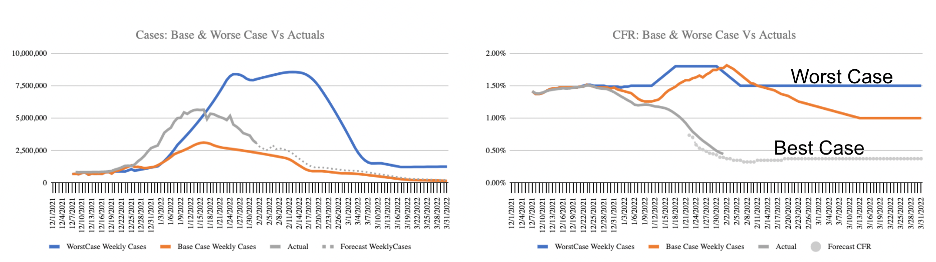

The bad news is deaths in January are up about 42% over December in the US. The good news is the US is trending on the best-case scenario for Omicron – it could have been a lot worse. The best case is to end Q1 with 992,336 COVID-19 reported deaths (or 181,883 incremental since the forecast on December 22nd). Compared to last year in Q1, when 205,619 died of COVID-19, the best case forecast would represent an 18% decrease in deaths.

(note: Solid gray line are actuals)

(note: Solid gray line are actuals)

The primary reason we are on the best-case scenario trend line is that vaccination protection has held up far better than expected. This has effectively kept vaccination deaths among fully vaccinated to about 9 per million per week. This is three times worse than a typical year of the Flu, but nowhere near the 137 deaths per million per week among unvaccinated. In total, January saw an additional 61,602 COVID-19 deaths, up significantly from the 43,488 deaths in December (up 42%), but fewer by half than my base case forecast.

When I built the base case in mid-December, the concern was Omicron would break through vaccination protection. We all know cases where Omicron has infected a fully vaccinated person, but vaccination protection from hospitalization and death has been far better than expected.

Denmark was the first to find that vaccination protection reduced transmission by half. A more recent analysis I performed using college data, where about 100% of students and faculty were tested in January, found vaccination and masking protection cut transmission by two-thirds. This goes a long way to explaining how the majority of the population dodged the Omicron bullet.

A window into a fully vaccinated society

Colleges represent a window into what a highly vaccinated society looks like. Historically, young people have been more likely to get and transmit COVID (see Oxford Study, September 2020). Colleges suffered significant disruption in 2020 as infections spread on campus and in dormitories. With the goal of returning to in-person learning, when vaccinations became available, most private colleges in the US required vaccination. Most achieved over 95% vaccination rates. Therefore, the return to campus in January was a moment of truth. Colleges such as Brown, Columbia, Reed, University of Portland, etc. required 100% of students to be tested upon return to campus in January. This means the positivity rate is the case rate since everyone is tested. For the US, total cases can be calculated using the case count and adjusting for the positivity rate, as demonstrated by Jeffrey Shaman, an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University. In other words, when the positivity rate shot up from 7% in mid-December to 30% in mid-January, it means cases were being undercounted by a factor of about four. In January, when the confirmed cases were 20,300,096, the actual infections, had 100% of the US been tested, were about 81 million, or 24.8% of the US infected with Omicron. Compare this to college statistics for January where the infection rate was about 8%. That is a two-thirds reduction in infections. That is a massive benefit from vaccination – far better than forecast.

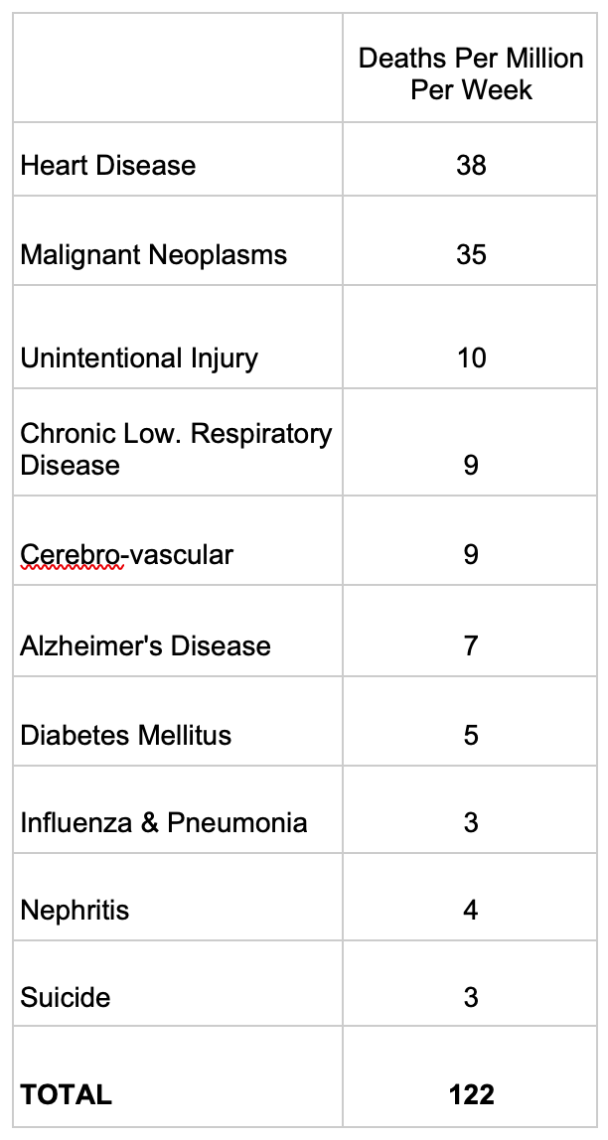

Unfortunately, the US as a whole is not as vaccinated as college campuses. Instead of 95%+ vaccination rates at Colleges, the US adult population is at 74.1% as of the end of January, and Omicron has been brutal to this unvaccinated population. Based on the most recent CDC measure of deaths among vaccinated and unvaccinated, and applying the 25.9% unvaccinated rate, deaths in January were 51,634 for unvaccinated (about 85% of all COVID deaths for the month). To put this in relatable terms, consider the top 10 leading causes of death in the US, according to the CDC 2018 report:

Source: CDC, 2018, all ages, US Census 328 million population estimate to calculate deaths per million per week.

Source: CDC, 2018, all ages, US Census 328 million population estimate to calculate deaths per million per week.

Among Unvaccinated, January averaged 137 deaths per million per week – more than the top 10 leading causes of death COMBINED. More than the total for the top 10 leading causes of death by 12%.

It isn’t just deaths. Hospitalizations among unvaccinated in January exceeded a quarter of a million. Each hospitalization creates challenges for families and economic costs to society. From a cost standpoint, the estimates of a hospital stay for COVID range from severity and by state. The lowest cost is the above-average vaccinated Maryland at $31,339 for non-complex and $131,965 for complex care (ICU). The highest is in below average vaccinated states, Nevada with $102,115 for non-complex and $472,213 for complex care. You can see the full list by state here.

Take in these costs for a moment. The costs are staggering.

Using an overall average stay of $75,000 per patient, unvaccinated patients generated over a quarter million hospital stays in January alone and over 1 million since vaccinations became broadly available over the summer, racking up a direct cost of $75 billion in the past six months.

A distributed approach, similar to insurance premiums for smokers, would see each unvaccinated person pay $1,800 per year for their cost. As with smoking, where there is a correlation between the choice and negative health outcomes, many unvaccinated may choose to remain so. So, how might an unvaccinated person get the signal that their choice has significant cost and risk associated with it?

A few insurance companies are now including an unvaccinated premium, similar to the premium paid by smokers for the average health costs per smoker. This takes the $150 billion in annualized cost of the unvaccinated and distributes it among the 25.9% of unvaccinated, which adds $150 per month per unvaccinated person to cover the predicted cost of hospitalization across the unvaccinated population. This is similar to the health tax on each pack of cigarettes.

But, the cost of being unvaccinated is more than the $1,800 per year per unvaccinated person to cover the hospitalization costs. We don’t know the cost of long COVID. Every time an infection occurs there is an opportunity for a variant to emerge. Variants like Delta and Omicron spread primarily from the unvaccinated. Our study of Delta in Washoe County in 2021 found that unvaccinated were 18x more likely to become infected with COVID and test positive. Omicron seems to follow this same pattern, with over 70% of infections transmissions from unvaccinated people.

Based on a brief study of Fox News content related to the pandemic, these facts are not generally known to the unvaccinated, who skew overwhelmingly conservative. The economic implications of a prolonged pandemic shift of consumer spending from services to goods are not addressed. The obvious link between the shift to goods and the supply chain woes and increased inflation is not discussed. Yet, they are the very real cost of the pandemic. Newly available antiviral drugs for COVID could lower the cost – each course of treatment is about $550 plus the cost of the visit to the doctor to have them prescribed. Still, far more expensive than $40 per vaccination dose, but much less expensive than hospitalizations.

Treatment after the infection doesn’t change the fact that the unvaccinated remain the majority of all cases – more likely to become infected and more likely to transmit infections, but it may address the problem of the unvaccinated filling hospitals and prolonging the associated costs of the pandemic (specifically the economic dislocation that has led to supply chain challenges and inflationary pressures).

Perhaps conservative state governors and legislatures that stopped vaccination and mask mandates in schools will reconsider given the overwhelming evidence that their states are doing far worse in terms of deaths over the past seven months compared to the states that supported vaccination and mask mandates. The mounting facts are that these policies cost lives and billions of dollars of taxpayer money. As a forecaster, I wouldn’t count on conservative states changing course. The scenario is for vaccination rates to stay about where they are trending. Having unvaccinated pay higher premiums to cover their costs, the same way smokers do, could be a market signal that might move the vaccination rate, but I suspect that the same Trump-appointed judges that stopped vaccination or test mandates in work environments and the same conservative legislatures that blocked mandates for schools would interfere with the free-market economic matching of choice and cost. In other words, there will be no economic feedback loop to signal to the unvaccinated that their choice is economically damaging. Instead, the cost will continue to be largely distributed and borne by the vaccinated who make up the super-majority of the population.

Since Omicron is adept at reinfections, the only hope is that each subsequent infection is less likely to lead to hospitalization or death, but the evidence so far is mixed. As In the movie Nine Months Robin Williams has a wonderfully hilarious role as a Russian vet who somehow gets a license to practice gynaecology among humans in the United States. His first patient is our heroine who is naturally horrified by the prospect, especially as he miscalculates her conception date by entering her as ‘simian’ into his computer program. In reality, however, to become a veterinary surgeon can actually be more difficult and time-consuming than becoming a doctor for humans. This is because the prospective vet has to master the physiology of any number of animals while the doctor only has one mammal to deal with.

What on earth, you ask, has this got to do in any way, shape or form with research, analytics, and insights?

The answer lies in our role in providing impactful insights into business issues. Two decades ago it could be argued that market researchers were more akin to vets than they are today. In those days, researchers had to master a wide array of methodologies, statistical techniques, and reporting formats to be able to answer any number of issues and deliver advice to their clients. In the modern world where, according to Lucid’s ResTech map, there are no fewer than thirty-three sub-segments to our industry, specialization seems more to be the norm. Furthermore, researchers and analysts tend to categorize themselves into sub-specialities – UX, CX, media, advertising, innovation, corporate reputation, social, political, retail… you name it. Are we perhaps becoming over-fragmented, overly tribal in how we classify ourselves? And is this helpful to clients who, after all, need answers and direction?

Is what’s good (and bad) for medicine good (or bad) for research?

Let’s imagine that you start to feel unwell. You go to your doctor and, in the majority of cases, you will see your family physician who is trained across the spectrum of diseases and conditions. Normally, they will be able to diagnose you and suggest a course of action. But in some cases, they will be stumped and refer you to a specialist, which is probably a good thing. But, in some circumstances, you may be struck by a condition that nobody quite understands. In which case, you are likely to be passed from specialist to specialist, each of whom comes up with a different diagnosis or worse, no diagnosis at all. What is missing in this situation is a synthesis of all the possible information and possibilities that could lead to a solution.

And so it is in research. In most cases, the issue is clear and it makes sense to bring it to a specialist. Which product concepts should we move forward with? How do we increase the impact of our advertising? Specialist researchers should indeed be the ones to whom you ask these questions. But what of situations in which the issue is more fundamental and perhaps less defined? Why is our market share falling? Why is our brand image lagging? Why is our new product failing to meet targets? The likelihood is that different specialists will give you different answers based on the lens through which they are looking and in which they are trained. Just as in medicine, what you need here is the capability to synthesize information from a variety of different sources as well as the ability to divine the story and the solution needed to resolve the issue.

Recognizing the need for balance

Ten years ago, Ian Lewis and I contributed the first part of a book called Leading Edge Market Research (published by Sage) in which we posited that there were two paths to a successful marketing research career:

· Generalists who are strong conceptual thinkers, strategic, future-focused, and change agents who understand the business. They need to become great consultants who seek alignment on key management needs, synthesize information from multiple sources, build strong relationships, tell compelling stories, and persuade management to take action.

· Specialists who align themselves with one or more of the numerous growth areas. Growth areas include consumer listening, advanced analytics (e.g. statistics, modeling, data mining, web analytics, media measurement & analytics), online communities, co-creation capabilities, business intelligence platforms, shopper insights, neuroscience/biometrics, behavioral economics, global and multicultural experts, ethnography & anthropology.

In later years, we changed the nomenclature of ‘generalists’ to ‘polymaths’ – people whose expertise spans a significant number of subject areas, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems.

To these two paths today, I would add a third that I would call ‘technicians’ – those that supply the technologies that enable data to be collected, collated, analysed, and displayed in ways that never existed in the past.

Once again, such a structure is not that dissimilar to that which we find in medicine – technicians, specialists, generalists (family physicians), and polymaths (and, yes, that includes vets as well as consultants). Each plays a vital role in answering today’s pressing business questions and all are important. But all need the basic underpinnings and training that lead to viable answers based on inaccurate data.

So, are we vets or doctors? Yes., Brown University Dean of the School of Public Health and a practicing MD reported in a recent tweet thread, the majority of patients he saw in his hospital with COVID were unvaccinated and previously infected. So, we remain in this bimodal pandemic, where unvaccinated die at a rate of 15x more than the vaccinated until production ramps up for the antiviral treatments.

Forecast vs actuals

In terms of forecast, credit where credit is due: IHME’s forecast was far more accurate than mine for January. IHME forecast was for 880,067, too low by only 8%. My base forecast, as noted above, was far too high for January. We are in line with my best case scenario, which projects ending the quarter at 992,356 while IHME’s forecasts end of the quarter a bit lower, with 967,234 reported COVID-19 deaths. For February, my forecast is to end the month with 961,110 reported COVID-19 deaths in the US.

Rex Briggs

Consultant and Author at Marketing EvolutionRex Briggs was named one of the dozen “best and brightest” in media and technology by Adweek, and one of the people to “watch and learn from” according to Brandweek. He has been honored with the Atticus Award for his work in direct marketing, the Tenagra Award for outstanding contribution to branding and ESOMAR’s Fernanda Monti Award for his work in CRM. Rex has also won international research awards for his work in understanding website effectiveness and online advertising. His work in understanding the effects of advertising in television, magazine and online was nominated for the prestigious John and Mary Goodyear Award for best international research. Rex was the first director of research for the Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB), and pioneered attribution analytics. His research has been translated into a half-dozen languages and he has taught at leading universities around the world.

Rex is the best-selling author of “SIRFs-Up – How Algorithms and Software are Changing the Face of Marketing.” The book tells the story of how brands can better optimize advertising spend with equations known as “Spend to Impact Response Functions” (SIRFs) and how they will become an integral tool for marketers of every size and vertical for allocating budgets and forecasting business results. Rex also is the best-selling author of “What Sticks: Why Most Advertising Fails and How to Guarantee Yours Succeeds.” The book draws learning from ROI measurement from 36 major marketers. The studies were designed by Marketing Evolution to track media expenditure in real time and offer solutions on how marketers can improve ad effectiveness. “What Sticks” was named the #1 marketing book by Advertising Age, and was featured on CNBC, Bloomberg, CNN, NPR and The Economist. Rex is an instructor for the Association of National Advertisers’ (ANA) School of Marketing, where he holds workshops on ROI measurement technologies and IMPACT Marketing.

Rex founded Marketing Evolution in 2000 and sold his interest in 2019. He is an independent consultant and author. Rex is known as one of the world’s leading experts in marketing ROI measurement and optimization technologies. His expertise derives from direct experience measuring and improving the performance of a wide range of marketing programs for more than 100 Fortune 500 marketers.

Article series

COVID-19 impact

- Making healthy habits stick after COVID

- Shobservatory Research Chronicles: Lockdowndiaries

- Capturing early stage consumer feedback, post-COVID

- Evolution of physical space in retail and hospitality

- November 2021 COVID-19 forecast & commentary

- Ethical brands in pandemic times

- November 14 reforecast due to OSHA rule stay

- COVID-19 December 2021 forecast for the USA

- Omicron

- COVID-19 forecast in the USA

- COVID-19 update for the USA

- COVID-19 Omicron retrospective

- Crises and community

- Research that makes a difference